A NON-CONFORMIST ICON – EILEEN GRAY

Remembering Eileen Gray. A woman who earned her status as an aristocrat of the design world in the male-dominated milieu of modernism.

Can a designer both define and deny modernism throughout their career? If the designer is Eileen Gray, she certainly can. Born in 1878 into a wealthy, Irish family, Gray completed her university education at the Slade School, one of the best art schools in England, specialising in painting. Gray was also one of the first female students admitted to the school. After graduating, she moved to Paris in 1902 and started working in the lacquer shop of a Japanese master. Japonisme, including lacquered furniture, was a strong influence on the prevalent Art Deco style of the time. Gray, combining the Far Eastern influences of her Japanese master with her own painting and design language, created products that were superior both in artisanry and appearance.

JEAN BADOVICI

Gray’s work caught the attention of the Parisian upper class, and in a city where women were practically invisible, brought a breath of fresh air to the decorative arts scene. In doing so, she laid the foundations for the next stage of her career. Gray, together with her partner, architect and architectural critic Jean Badovici, opened a showroom called Galerie Jean Désert. In the gallery, she exhibited lacquer work and took commissions to do interior decoration.

THE BIBENDUM CHAIR

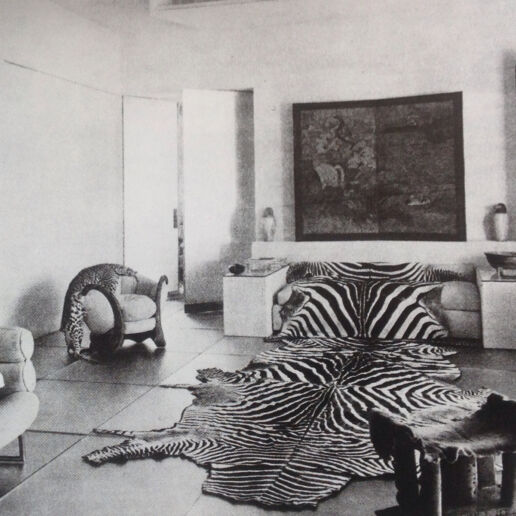

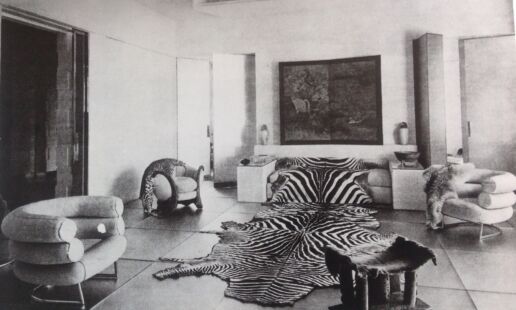

Designing interiors for fashion designer Suzanne Talbot became a cornerstone in her career. Talbot’s house, a textbook example of French Art Deco style with exotic patterns and animal furs, was a masterpiece. The problem, however, was that Gray never held the Art Deco style close to her heart. For the Bibendum Chair, one of the pieces she designed for Talbot’s house, Gray used tubular metal legs and a curved body. The Bibendum Chair was one of the first, if not the first, instances of the use of metal tubing in furniture design, but it would later become a star of the mid-century modern style.

Gray’s next decoration project came from Rue de Lota. Gray admired the building in which this apartment was located and, at this midpoint in life, fell in love with architecture as a practice. Although she had no training, she began to devote the time she usually spent on lacquer work to architectural drawings, and with the encouragement of Jean Badovici, embarked on a new creative era.

GRAY’S INSTINCTIVE ARCHITECTURAL STYLE

Gray’s first architectural project, the house in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, still makes even the most iconic modernist architects envious. The beauty of the project was hidden in plain sight:she designed E-1027 as a space that would serve its inhabitants. While modernist designers emerging from World War I were searching for an answer to the post-war quest for hygiene and simplicity, Gray added to it a human factor. Designing the architecture of the house and all the furniture inside with the understanding that ‘form follows function,’ Eileen Gray, also added ‘user experience ‘ – a concept not yet established in design jargon at that time – to her designs.

And yet, throughout her years of active production, Gray was overlooked in a design world dominated by men. This unique woman, who was more inventive than her colleagues and before her time, isolated herself toward the end of her career. Until rediscovered! In 1972, when Gray was 94 years old, art historian Joseph Rykwert mentioned her creativity and innovations in an article he wrote. Thanks to this article, Gray was brought back onto the world stage again, receiving perhaps the most unforgettable offer of her life a year later. When a furniture company contacted her to ask if they could reproduce her designs, Gray asked, “Do you really think they’re worth reproducing?” The answer was undoubtedly a yes, so the gears started turning.

LAST YEARS

Gray finally had the recognition she deserved, if only for a few years. She passed away in 1976 at the age of 98, considered a visionary. After her death, her fame only multiplied. Countless exhibitions were mounted, devoted to her and her work.Books were written and biographical films were made about this humble woman. We remember this giant of modernism with endless respect and adulation once again. She continues to inspire men and women from all over the world with her design language and modesty. Many are grateful that she shaped this world while passing through it.

"The future is bright, only the past is cloudy." —Eileen Gray

Eileen Gray 1878-1976

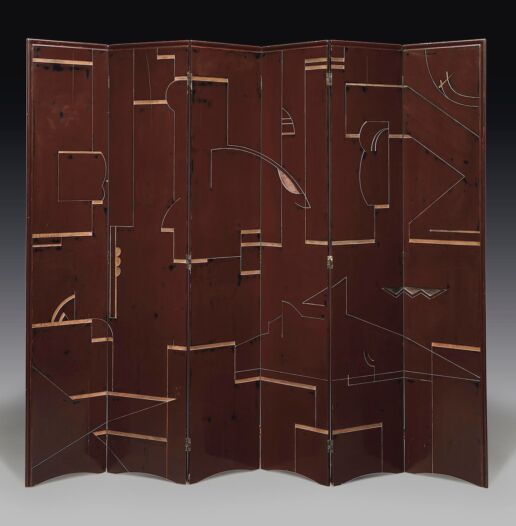

Eileen Gray primarily designed screens in her lacquer workshop. This screen, believed to be produced between 1922-1925, found a buyer at a Christie’s auction in 2012 for $1,874,500.

In the living room, Gray’s Dragons Chair was designed for Suzanne Talbot’s house along with the Bibendum Chair, the designer’s first nod to modernism.

Another piece designed by Gray for Talbot’s house, the Bibendum Chair, is one of the first products to feature tubular metal construction in a piece of furniture. Bibendum embodies Gray’s signature combination of Art Deco and modernism.

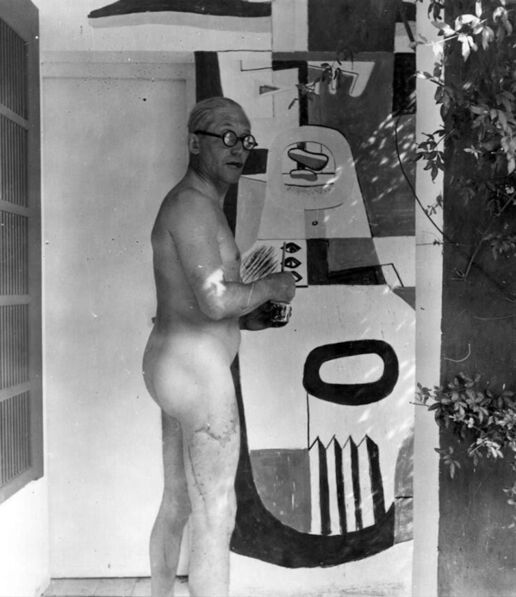

Gray, as she was completing her E-1027 house in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in 1929, at the age of 51. The open plan house, with moving glass panels on the exterior walls and movable furniture, became a unique example of its kind and for its time. Gray, who lived with her partner Jean Badovici in the Cap-Martin house (E-1027 is a coded combination of their names), also drew the attention of Le Corbusier, a close friend of Badovici and someone with whom Grayoccasionally collaborated. Corbu visited the couple frequently and was known to take great pleasure in the house itself. Although he was not given a standing room here, he bought the land adjacent, in order to always be nearby, and attached a cabin to it. It remains controversial whether it was Corbusier who influenced Gray’s work or vice-versa.

The E-1027 house consists of a rectangular mass raised off the ground on columns. The house, included on the French National Heritage list, has been open to visitors as a museum since 2015.

The main volume of the E-1027 house faces the sea and serves as a bedroom. Here, the carpets and movable furniture were designed and produced by Gray herself. (Photo by Manuel Bougot)

In the open plan house, areas serving discrete purposes are lined up one after another. It’s possible to see a dining table with chrome-framed chairs beyond the main living space and bedroom. (Photo by Manuel Bougot)

The E-1027 table, designed by Gray for her own house, is one of her most recognisable pieces of furniture. She built the table using two of the most popular materials of the time: metal and glass. The designer, once again emphasising the human factor, made the table’s height adjustable because she didn’t want her guests to spill crumbs while eating in bed.

When Badovici and Gray separated in 1932, Badovici became the sole owner of E-1027. Despite Gray’s many requests to the contrary, Badovici allowed Corbusier to paint murals on the interior walls of the house. Painting in the nude, Corbusier changed the face of the house and, in later years, admitted that his work had not improved it. In 1956, when Aristotle Onassis offered to buy the house, Corbusier, who had already claimed ownership of E-1027, asked a friend to buy it instead in order to retain ownership of his artwork. In 1965, Le Corbusier suffered a fatal heart attack while at sea on Cap-Martin, where the house remains standing, having survived Corbusier’s obsession, the Nazis and looming dereliction.

Gray in 1973 during a meeting with the furniture company, Aram Designs Ltd., London, to discuss bringing her drawings back to life.

The N71 table lamp, designed by Gray in the early 1940s during her Art Deco period in Paris, is currently for sale at Sanayi313 in black and chrome colour options.