CONCRETE

The Constitution of Concrete

Stemming from a need for communal living areas, humans embarked on a quest to create indoor spaces which started in caves, progressed to concrete buildings and culminated in skyscrapers.

Primitive versions of mortar which included lime and plaster first appeared around 3000 BCE. This mixture was originally used in the making of the Pyramids of Egypt and later the Great Wall of China. Concrete and reinforced concrete was introduced in the 19th century. A rudimentary form of reinforced concrete was invented by a gardener who came up with the idea of adding iron bars into concrete to produce stronger flower pots. The world of construction took a whole new turn when in 1902, French architect Auguste Perret constructed the world’s first building to use pillars, girders and flooring.

Concrete is the mixture of aggregate, Portland cement and water. Listed like this makes it seem simple however, the formula has a direct effect on the strength, appearance and lifespan of the material. Aggregate is a mixture of sand and gravel which are the raw materials used in the making of concrete. Portland cement is what gives the grey colour typical of concrete. The name originates from the similarity in colour to the limestone found in the Portland Peninsula in Britain. Grey and white cement are the two most common variants used in buildings and products.

As the main constituent of construction and architecture, concrete is both a load-bearing component and a building material. It is used extensively in the construction of buildings, dams, canals, roads and bridges yet, it is also an indispensable material in the making of decorative objects, furniture and various artwork. The popularity of concrete stems from its properties as a resilient, fire-resistant, waterproof, cost effective and energy efficient material.

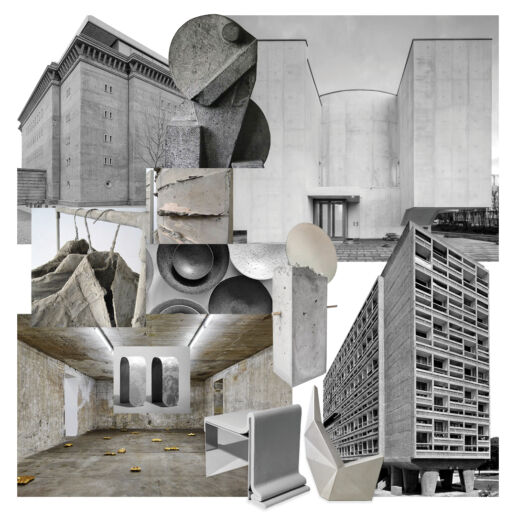

‘Raw concrete’ is one of the diverse applications of concrete. The original French term ‘Béton Brut’ literally means raw concrete. The first example of raw concrete can be seen in German architect and city planner Max Berg’s building ‘Jahrhunderthalle’ which was completed in 1913 in the German city of Bresslau. In this building, concrete was applied as it came out of the mould, without any additional outer cladding. Raw concrete is composed of unprocessed concrete surfaces, yielding a natural, unfinished appearance. It is possible to add colour to raw concrete with pigments or create various patterns and textures with the help of moulds and applications. Raw concrete is cost effective, ideal for creative solutions and time saving as there is no need for plastering or cladding making it appealing for architects and artists alike. Raw concrete became the signature material of the Brutalist movement which advocated the exposure of every component in a building. The style gained popularity in Turkey towards the end of the 1950s.

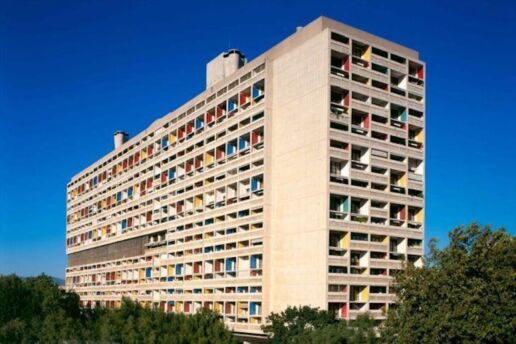

Brutalism

The Brutalist architectural style spread very quickly mainly due to the housing deficiency and economic constraints of the post WWII era. As a cheap and quickly processed material, raw concrete became the ultimate answer to these pressing problems. Yet, the style was criticised by some circles for being ugly, crude and soulless. Brutalism enjoyed the peak of its popularity during the 50s, 60s and 70s but choices gradually changed during the 1980s. The most famous example of the Brutalist style is undoubtedly Unite d’Habitation (Housing Unit) that was designed by Le Corbusier in the early 1950s. During construction, Le Corbusier used raw concrete straight of the mould and in doing so managed to design an architectural structure comprised of repetitive and harmonious geometrical shapes. Futurist architect Zaha Hadid’s more recent ‘Pierres Vives’ building stands out as another example of an aesthetic perspective pioneered by Le Corbusier.

Historically speaking, concrete was the main building component of the Brutalist movement yet, there are numerous examples that incorporate various other materials such as glass and steel. In the architecture of ‘Centre Pompidou’ (Pompidou Centre), Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers attempted to give the building a modernist style by completely exposing building materials. The prominent names of the movement include names like Marcel Breuer, Erno Goldfinger, James Kalisz, Bertrand Goldberg and Fernand Boukobza.

The use of reinforced concrete, which dates back to the beginning of Modernism, spread further with various artistic approaches that emerged throughout the 20th century. Pioneers of the modernist era, namely Le Corbusier Pierre Luigi Nervi, Oscar Niemeyer and Tadao Ando employed reinforced concrete to design thin section columns, wide and extensive frames, surfaces with large voids, folded plaques and shell cladding.

The Bunker – Christian Baros

The Bunker – Karl Bonatz’s historic building in Berlin that was completed in 1943 – was transformed into a gallery by Christian Baros to exhibit his growing art collection. The Bunker must be one of the best examples of raw concrete application. The gallery does an impressive job of displaying modern art with concrete ceilings and walls in the backdrop. This building convinces me that the use of concrete in interiors is a suitable background which helps emphasize other visual elements inside a space.

Concrete and Art

Concrete is also a flexible, fluid and mouldable material which provides plenty of room for artistic expression. A unique example of concrete in art is Benoist Van Borren’s sculptures in which he toys with geometric forms. The minimalist sculptures of this architect with an artistic streak are some of the best in brutalist sculpture. Another artist worth mentioning is New York based Eric Sommer and his creations made of cement and concrete. A surreal questioning ensued when he presented a concrete encrusted second-hand Volvo 240 car inside a container. ‘Concrete Car’ was featured at New Jersey’s Mana Contemporary.

There is a wonderful quote by architect Louis Kahn, whose impressive ‘Re-framed’ exhibition was hosted at Pera Museum in 2017: ‘A space in architecture shows how it is made’. This reconfirms my conviction that brutalist structures have no details to conceal, fully exposing the design without reservation; not to mention that concrete is the best material to express a genuine architectural design.