A 1500-YEAR-OLD RELIC

The renovation project of the Monastery of Stoudios promises to shed more light on Istanbul’s rich history. Archaeologist and art historian Murat Sav, who is in charge of its restoration, elaborates on the landmark building, which was probably completed in the year 463.

PAPER: Before we delve deeper into the history of the Monastery of Stoudios, could you tell us more about the restoration project? Why was the monastery never restored until now?

MURAT SAV: The monastery suffered severe damage in the 1910s, which caused a significant part of the roof to collapse. Unfortunately, this happened during the final years of the Ottoman Empire, during which the building seems to have been overlooked. Remember that this was a period of great turmoil. The Balkan War, the Italo-Turkish War and, more importantly, World War I were wreaking havoc across the region. Restoring an old monastery was, understandably, not on the list of priorities. Following the proclamation of the republic, Turkey focused on post-war redevelopment, but that was disrupted by World War II even though the country remained neutral. In 1944, by the decision of the Council of Ministers, the monastery was handed over to the Ministry of National Education to be repurposed as a museum. The first initiative to save the building took place in 1955, which saw a series of reinforcements to the upper sections of the main walls, however, no conservation projects were begun. It took another decision by the Council of Minister, much later, in 2012, for the building to be turned over to the General Directorate of Foundations.

P According to historical sources, the Monastery of Stoudios is the oldest religious building in Istanbul. When was it built? Who was in power back then?

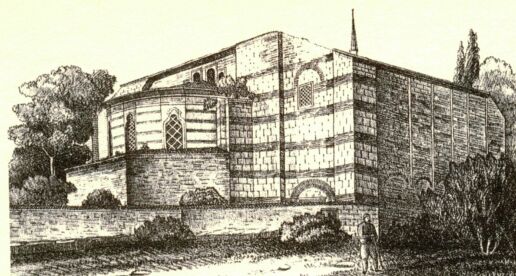

MS The Monastery of Stoudios is the oldest surviving religious building within the ancient walled city of Istanbul. It was completed in 463 C.E., 1,561 years ago. I think no one will find this short of remarkable.

Regardless of function, several factors are required to keep a building in use uninterruptedly for so long. A timeless purpose and frequent repairs are key to making this possible. The building was used as an Orthodox church until the Sack of Constantinople (following the Fourth Crusade) in 1204 when it was first plundered and then abandoned for 57 years. In 1261, the building once again assumed its Orthodox identity until the 1480s, when it was converted into a mosque within an Islamic monastery complex by Sultan Bayezid II and remained as such until the 1940s.

In other words, we are able to trace a continuous sequence of functions and repairs through the life of this building. The small rooms in the courtyard, which no longer exist, were occupied by Orthodox monks during the Byzantine period. The monks were replaced by dervishes when the church was converted into an Islamic monastery under Ottoman rule. Similarly, the religious manuscripts and miniatures produced in buildings affiliated with the monastery were replaced by studios for the practice of Islamic calligraphy during the Ottoman period.

The name of the monastery complex appears frequently in historical records. It took its name, originally, from Stoudios, the person who commissioned it, but the church is consecrated to Saint John the Baptist. According to the Bible, John the Baptist was first imprisoned and then killed. A skull, rib fragment and arm bone believed to belong to Saint John were also preserved in the crypt in front of the apse of the church.

When the worship of icons was prohibited in 726, however, during a very stormy period of iconoclastic dispute, the monastery’s devoted monks were driven away, to other monasteries along the Bosporus, when they violated this new doctrine. Locally, the complex was called the ‘Monastery of the Unsleeping’ since its monks only prayed when deprived of sleep.

During the Ottoman period, the Ottomans and Byzantines would exchange princes as hostages, a gesture of goodwill and trust. Rumour also has it that Sultan Bayezid I’s son, Prince Kasım, converted to Orthodoxy and was buried in the narthex of this monastery. Much later, during the 18th century, the distinctive semi-dome of the apse was severely damaged by an earthquake and then destroyed in a subsequent fire. This section had to be rebuilt, to a great extent, by the Ottomans.

P: What are the key features of the monastery in terms of Roman Imperial architecture and the religious architecture that followed?

MS This building has appeared on the maps of Istanbul since the 15th century. These maps, and some Byzantine and Ottoman miniatures, make it possible to trace the evolution of its roof cover in particular. The monastery had its own ‘typikon’, a liturgical book of instructions, practices, and hymns of the Divine Liturgy. Aside from detailed information on rituals and practices, this comprehensive document also indicates that the monastery took in important revenues. This typikon set an example for subsequent monasteries. A similar document from the Ottoman period, prepared in the name of İmrahor İlyas Bey in 1504, also indicates significant revenues. The Monastery of Stoudios is actually a basilica that dates back to the Hellenistic period, but its real development took place under Roman rule. Basilicas were built by emperors until Christianity became the official religion. With the spread of Christianity, these massive, mostly East-West-oriented structures were used as churches because they could accommodate large congregations. Soon, this became one of the most common church layouts of the early Christian period. The Basilica of Stoudios is a good example of such early Christian buildings. In fact, it is a successor to Roman architecture in terms of its structure, appearance, plan and design. This building is also one of Istanbul’s few original Roman structures to have partially survived to the present day. Therefore, conservation methods must consider this extremely wide range of influences, world views, and details.

P How long is the restoration going to take? How will the building function once the project is completed?

MS As mentioned, the building was converted into the İmrahor İlyas Bey Mosque. The actual restoration phase has not yet fully begun because revisions are being made to the existing project based on recent investigation and analysis. It is not easy to predict much about the restoration process of ancient buildings. Surprises that can cause significant delays are always just around the corner, sometimes literally. You also have to take into account findings from new analysis, research and excavation that might require revisions to the project. All these are decisive factors in the process.

In cases like this one, the quality of the work is more important than the time it takes to complete it. Once finished, it will probably be used as a mosque – maybe a better term will be a museum/mosque. For example, I think it is crucial that the floor mosaics of the cella remain open to visitors in order to give the public a better idea of the building’s Byzantine and Ottoman features. In my opinion, its function as a mosque could be symbolic. To be more specific, the south nave, which does not have its original paving, could serve religious purposes while the mosaics and other details can remain on display.

This project could showcase a whole new understanding of conservation in terms of allowing multiple functions to co-exist in a single complex. Keeping in mind its function as a museum: I think the architectural features, including the courtyard, should be emphasised with landscaping to add natural elements and make it more picturesque. The traditional Byzantine and Ottoman details should be preserved while minimising new interventions. Remember that this building was first a Roman basilica that was later used as a church, mosque and monastery for not one, but two, religions.