YILDIZ MORAN’S MARDİN, 1950’S

Yıldız Moran; the first professional woman photographer in Turkey to receive formal academic training in her field, is deepening our pages with the photographs she took back in the 1050’s in Mardin that are exhibited in the 6th edition of Mardin Biennale for the first time.

Deniz Türker; an historian of Islamic art and architecture and a graduate of Harvard University’s dual degree program in the History of Art and Architecture and Middle Eastern Studies wrote about how Moran’s “ability to ‘frame’ visual narratives” came to life in Mardin.

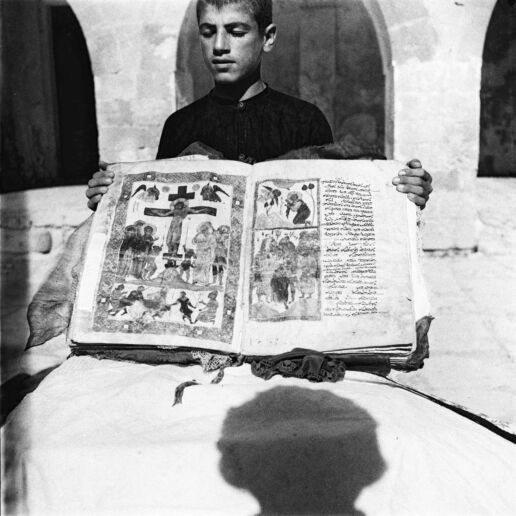

Türker, in her article points to the photograph that ornaments Sanayi313 PAPER #05’s cover; which is Yıldız Moran’s only photograph where she catches her own shadow. In the photograph, there is a young orphan boy with damaged eyesight who is holding an Syriac manuscript. As Türker talks about the photograph, we come to realise that this boy should have captured Moran’s heart so much that she appears as a shadow in the portrait.

Yıldız Moran arrived in Mardin sometime in the late 1950s. She was not traveling alone. She was often the only woman, in her early twenties, among a scholarly team of men. Every year when Istanbul University closed its doors for the summer, a dedicated group of scholars from different disciplines (history of art, literature, cinema, archaeology) would embark on their predetermined Anatolian tours. Often the leader of the group was Moran’s uncle, Mazhar Şevket İpşiroğlu, the German-trained philosopher of aesthetics and art historian, then a pivotal figure in the burgeoning humanistic fields in the university. Some of these trips resulted in award-winning documentary shorts in international film festivals: a silver Bear for the 28-minute, black and white documentary, “Hittite Sun”, in the Berlin Film Festival of 1956 held pride of place.

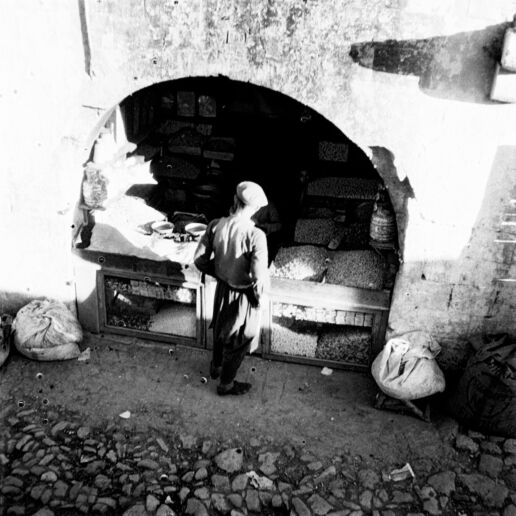

Some of these trips are better documented then others, occasionally but not consistently celebrated in the university bulletins, while others still await their turn to be discovered and charted from among the university’s archives. The tour that included Mardin is among the yet undocumented ones, but judging from the itineraries of Moran’s photographic archive, the group must have also visited Urfa, Batman (her presubmersion images of Hasankeyf, in their eerie bygoneness, seem to foresee and mourn the future deluge), Bitlis, and Diyarbakır. She celebrated ordinary life; two women stacking logs, among the grandeur of historical ruins, while a sliver of local fauna is caught in the frame.

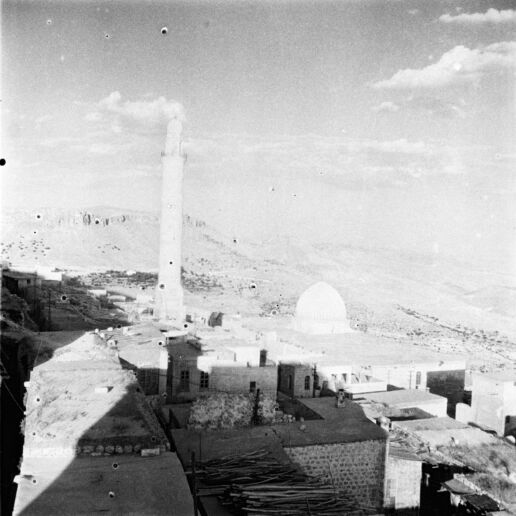

There is no denying that Turkey’s east and southeast were largely foreign to the Istanbulite group. They encountered severely underpopulated, under-resourced towns, post imperial and postwar landscapes, and historical remains that spoke to regions beyond the newly demarcated borders. The soft glow of Mardin’s saffron-colored limestone, its pliable carvability into latticework, the town’s command with its terraced houses, over the breathtaking Mesopotamian landscape from the southern cliffs of a mammoth rock, were to be documented. The group members were constantly driven by a documentary impulse; the findings were always subject to becoming scholarly books, semi-touristic brochures, and experimental cinematic shorts.

Moran had practice in photographing the architectural whole, but she particularly loved the close-up details. Her photographic tour of Europe after completing her studies in London and before coming back to Turkey, especially her time in Andalusian cities, enabled her to study and capture elaborate surface decorations. Did she make connections between the arabesque designs on Alhambra’s stucco walls, and the glittery mihrab of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, with those on the contemporaneous scalloped stone mihrab of Mardin-Kızıltepe’s Great Mosque? I have no doubt she did.

Another, lesser-known fact tied her closest to Mardin of all the unfamiliar towns she passed through and photographed. Her favorite portrait photographer, Yousuf Karsh (d. 2002), the Armenian Canadian artist was born and partly raised in Mardin, during the most calamitous time in the region’s history. I will leave Karsh to describe early-twentieth century Mardin in his own words, which must not have escaped Moran and her academic travel companions:

I was born in Mardin, Armenia, on December 23, 1908, of Armenian parents. My father could neither read nor write, but had exquisite taste. He traveled to distant lands to buy and sell rare and beautiful things — furniture, rugs, spices. My mother was an educated woman, a rarity in those days, and was extremely well read, particularly in her beloved Bible. Of their three living children, I was the eldest. My brothers Malak and Jamil, today in Canada and the United States, were born in Armenia. My youngest brother, Salim, born later in Aleppo, Syria, alone escaped the persecution soon to reach its climax in our birthplace.

It was the bitterest of ironies that Mardin, whose tiers of rising buildings were said to resemble the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and whose succulent fruits convinced its inhabitants it was the original Garden of Eden, should have been the scene of the Turkish atrocities against the Armenians in 1915. Cruelty and torture were everywhere; nevertheless, life had to go on—albeit fearfully—all the while. Ruthless and hideous persecution and illness form part of my earliest memories: taking food parcels to two beloved uncles torn from their homes, cast into prison for no reason, and later thrown alive into a well to perish; the severe typhus epidemic in which my sister died, in spite of my mother’s gentle nursing. My recollections of those days comprise a strange mixture of blood and beauty, of persecution and peace.

So, when visitors to the Mardin Biennial are viewing Moran’s photographs, especially but not only her portraits, they ought to be aware of the layers of the photographic trade. In Mardin, Moran is paying an homage to Karsh, Mardin’s talented son, whose work must have never traveled to his hometown even at the height of his worldwide popularity when he was shooting the likes of Churchill, Picasso, and Hemingway, but better yet Martha Graham, Marian Anderson, Georgia O’Keefe.

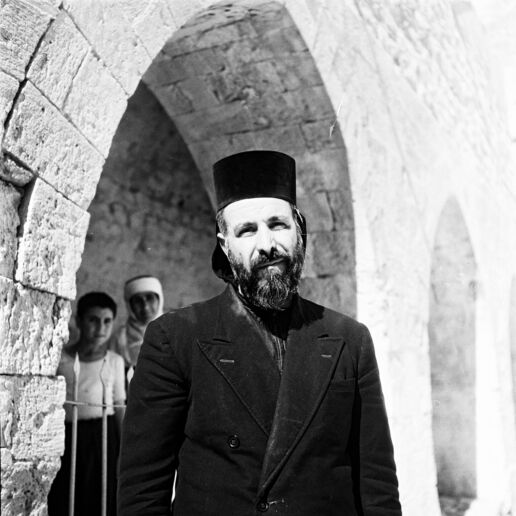

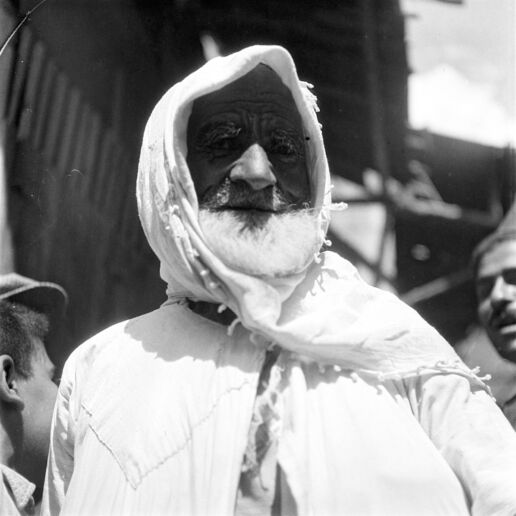

There are two protagonists in Moran’s Mardin portraits. Cebrail Allaf, the Syriac monk-priest and head of the Deyrulzafaran Monastery, who was known for his beautiful singing voice, deep knowledge of the region’s many languages (Aramaic, Arabic, Kurdish, Turkish, classical Greek and Syriac), and the monastery’s rich collection of manuscripts, appears in front of Moran’s camera, with a gentle, generous smile, or in the act of guiding his visitors. The other one is a young boy, who is made to hold an illuminated Syriac manuscript, displaying Christ’s Crucifixion. It is a rare photograph where Moran catches her own shadow. The boy’s gaze is averted, not just because of the holiness of the subject he holds in his hands, but because he has damaged eyesight. He was also an orphan left at the door of the monastery at age 10, who would grow up in the monastery under the watchful eye of Cebrail Allaf and guard the door, awaiting the return of his mother, and, in the process, become the site’s symbol. Young Bahe, nightingale in Syriac, captures Moran’s heart enough for her to appear as a shadow in his portrait.