FACT OVER FICTION

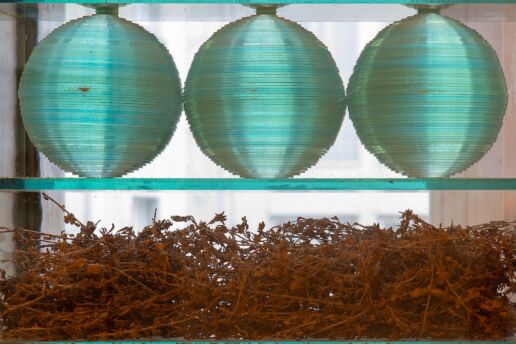

Handan Börüteçene’s Istanbul is as colorful as her imagination, and her work on the city keeps a record of the past at the convergence of reality and art. Open until April 14 at Salt Beyoğlu, her ‘Realm of Three Inland Seas’ exhibition is a unique opportunity to travel through the city's history that goes back thousands of years.

Handan Börüteçene feels a passionate connection to Istanbul. It is as if she is the only person in charge of the fortification walls, the ruined palaces, the remains of ancient civilizations waiting silently underground. Take the Quadriga Horses that were dismantled from Sultanahmet Square and taken to Venice centuries ago, for example. Börüteçene believes that nothing dies. She listens to everything that radiates energy and pursues what is lost. She knows all about the city that has been plundered numerous times over the centuries.

I met with the artist at Salt Beyoğlu to talk about her exhibition featuring a selection of works that portray both the ” Realm of Three Inland Seas ” and the thousands of years of Istanbul’s past. Strong southerly winds were blowing that day in Istanbul. I realized again that any detail about this city evoked something in her.

I met with the artist at Salt Beyoğlu to talk about her exhibition featuring a selection of works that portray both the ” Realm of Three Inland Seas ” and the thousands of years of Istanbul’s past. Strong southerly winds were blowing that day in Istanbul. I realized again that any detail about this city evoked something in her.

‘Istanbul is a city of peninsulas divided by a strait and delimited by two inland seas,’ she begins. ‘Istanbul is flat except for Architect Sinan’s masterpiece, the Süleymaniye Mosque imposing over the landscape like a mountain. These topographic features also determine the prevailing winds. The northerly Boreas, the southeasterly Eurus, the northwesterly Argestes… But first and foremost, it is the southerly Notos winds that are the most upsetting for the inhabitants of Istanbul, including birds, cats, and people. Notos makes you weary, restless, and irritable. That is why, from the Roman times until 1984, when capital punishment was abolished in Istanbul, death penalty hearings were postponed if Notos was blowing that day.’

The things she says are hard to put into perspective today. We travel back in time to her childhood as if we were wandering through a period movie set. She spent her early childhood in Yıldız, a neighborhood that developed around the Ottoman Imperial Yıldız Palace. She lived with her family in a house with a garden before former Prime Minister Adnan Menderes opened Barbaros Boulevard, dividing the neighborhoods of Serencebey, Abbasağa, Beşiktaş, and Yıldız. She cannot remember much about her grandfather’s house, which was demolished to open up the boulevard, but she vividly recalls the social fabric of the neighborhood. Take the concubines in the Harem who were shown the door with the abolition of the caliphate after the proclamation of the Republic in 1923… Circassian Adviye Hanım, who smoked her pipe lavishly, or Italian Dilruba Hanım, who wandered the neighborhood with a shawl thrown over her white hair…

‘I grew up in that neighborhood with people from all religions and races. I still feel uncomfortable making such distinctions. We had no idea of these issues back then. No one would feel alone, estranged, or marginalized. Holidays and festivities would never end. We celebrated Kandils, Easter, Christmas, and Eid together. We moved to the Etiler district in my last year in primary school. Today, Etiler is considered downtown, but at the time, it was a remote rural area where packs of wolves would come looking for food. I used to ride horses where Akmerkez Shopping Mall stands today. Pine nut forests stretched from Levent High School all the way down to Bebek. Flower fields occupied the whole of Akatlar; flowers grown there were sold all over Istanbul. Arnavutköy was full of gardens where its famous strawberries were grown. In the summer, we would go to visit my aunt in Tarabya. That is where I learned to swim. We would swim in the bay with fish and the marble harbor paving of ancient Therapia glistening on the seabed…’

She has recorded almost every detail of Istanbul in her memory, including its myths and stories, astonishing history, buildings, geology and flora, poets, archaeologists and architects, museums, and excavation sites, and she keeps these details alive in her work.

‘Back in primary school, I remember having a strong desire to lift all the layers of the city to investigate each one in detail. I wanted this, especially for the Hippodrome in Sultanahmet. My brother used to tell me the history of every building like a fairy tale. As we walked up the ramp to the upper floor of Hagia Sophia, he would exclaim, “Make way and bow respectfully. Look, Theodora is going up on her horse.” You never forget when stories are told like this. You are left with vivid visual memories. Especially the horses! We would stand where the Quadriga horses once stood and stare at the sky. I would pretend to fill in the missing horses in the air with my finger.’

Börüteçene has been obsessed with the Quadriga horses for years. She believes the replicas, if not the originals, will be on display at the Hippodrome one day. If that weren’t the case, would she wander around the city’s historical quarters with the ghost of Istanbul created in the person of Moiro of Byzantium, the oldest recorded poet of the city? Or would she come up with a sculpture series based on her conversations with Hagia Irene, the church she visited almost every week for a year?

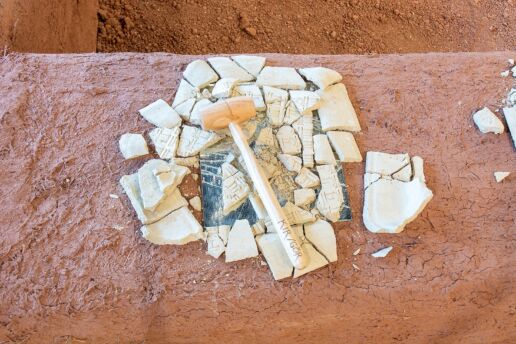

In fact, imagination is one thing, but its friendship with knowledge is another. That is what we call art. ‘I used to nag my historian and archaeologist friends, claiming that neolithic settlements in Yarımburgaz and Fikirtepe left no doubt that neolithic people inhabited ancient Istanbul. They always thought it was my artistic imagination at work. You should have seen them when a neolithic layer was discovered in Yenikapı… So, it was real, not a figment of my imagination.’

She compares Istanbul to a dowry chest. But the object of concern is not the chest itself. It is about the city that looks like it has been forgotten, left under multiple layers, all its beauty buried under it. She has been lifting off those layers and diving into that chest throughout her artistic career.

‘But how can people go so extreme in taking the city for granted? Why are they so afraid of a city’s past?’ she asks. However, there is one thing she is sure of: ‘Istanbul is the most beautiful city in the world. That spirit will never die no matter what they do, and she will always continue to surprise us. We are talking about a place inhabited uninterruptedly by humans for the last 400 thousand years.’ She has a strange ritual she repeats invariably before she leaves the city – going to Süleymaniye Mosque and entrusting the city to Sinan.