HIROSHI SUGIMOTO – On Looking and Seeing

Hiroshi Sugimoto is an artist who uses the frame to reflect what is happening in his inner world instead of capturing what is happening around him. He seems to take photographs without even pressing the shutter button, pushing the boundaries of physics using complex mathematics and exploring the unknown depths of light sources. For the last fifty years, people have been fascinated with the works of one of the most iconic photographers of our time.

I was in London last November, staring at the long list of exhibitions I wanted to see, when I received a text from Rana, the director of GaleriNev Ankara. It read: “You can’t leave without seeing ‘The Mother & The Weaver’ exhibition at the Foundling Museum and Sugimoto at the Southbank Centre!” I was sure that an exhibition that excited Rana would please me, too. Undoubtedly, black and white photographs would be much better than being out in the icy cold London weather, so I headed to the Hayward Gallery…

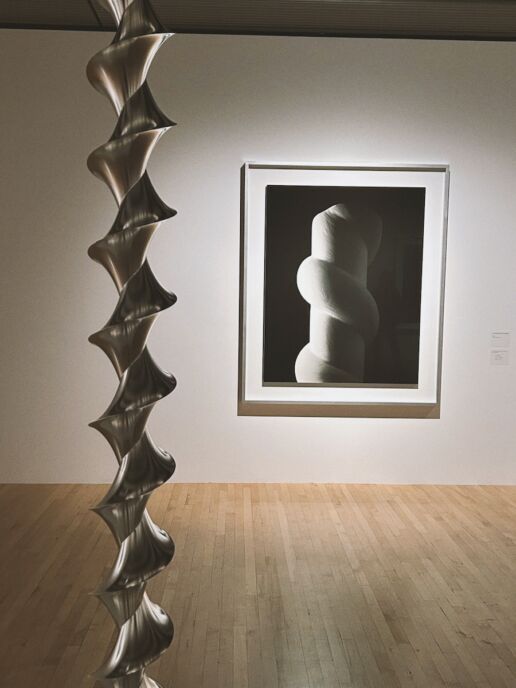

Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in Japan in 1948. He got involved in photography in the 70s and spent a life between Tokyo and New York pursuing his art, which gradually expanded its scope to include architecture and sculpture. Here I am, at the most comprehensive exhibition ever of the acclaimed artist. I notice something within the first ten minutes of walking in the hall. Everyone slows down visibly, spends ample time observing, and constantly changes positions to catch a glimpse from different angles. Sugimoto has the unique ability to miraculously slow down and prolong the viewing process, whether with sculptures or oversized black-and-white photographs. He believes that the act of looking itself is a process of discovery. Photography is a tool for the artist that allows him to stop time and look deeper into the issues that he finds important. According to him, this is a process of invention, not documentation. Sugimoto took the ‘Dioramas’ series while still working as a photography assistant in New York. This was also when he started to see himself as an artist for the first time. Going further back, Sugimoto was a curious child. At age 12, he laid claims on a Mamiya 6 camera his father never used. He quickly learned its functions and set up a darkroom in his dressing room. Photography had already become a hobby he was passionate about. The animal dioramas he saw displayed in the New York National History Museum when he was 20 blew his mind. The stuffed creatures posing in front of fake backdrops pushed Sugimoto to question the concepts of life and death and the past and the future. He started experimenting with photography as the perfect medium to record history and the expectation that everything seen in an image is real. He spent long hours in the museum, looking for ways to depict these animals alive with his 19th-century camera. By constantly manipulating the camera’s aperture settings with exposures of 20 minutes, Sugimoto discovered a method to distinguish between a polar bear’s lifeless white fur and the snowy white background, making it appear as if it were blowing in the wind. Today, these blown-up photographs, reaching two meters in length, leave the viewer on the fine line between life and death, just like they did to the artist nearly 45 years ago.

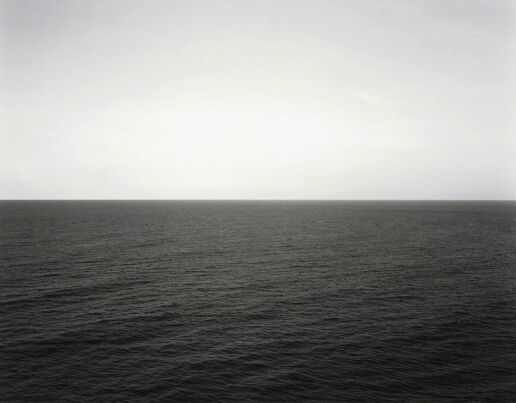

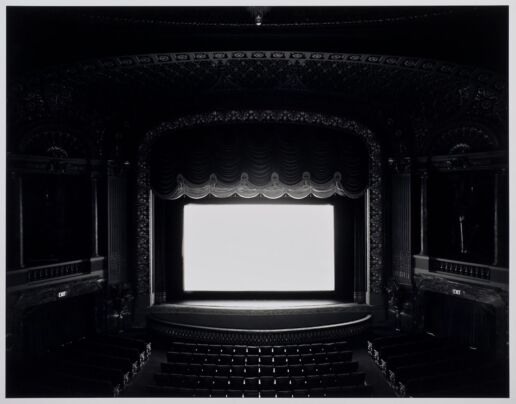

Using his technical expertise in classical photography, Sugimoto rediscovers the power of the art in capturing the invisible but fundamental forces in the world we live in. His work converges around the themes of time, metaphysics, and empiricism. ‘Theaters’ and ‘Seascapes,’ two of his most iconic series, seem to consolidate time into a single image while traveling through time with photography. Featuring long-exposure photographs taken in classical movie theaters, each shot in ‘Theaters’ was exposed for the duration of the film projected on the screen. As the only light source in the middle of a dark and impressive hall, the white screen actually contains thousands of images inside it. ‘Right in the middle of the picture, you see an uncanny absence and a bright and commanding presence! Meanwhile, time is reborn within itself at an astonishing speed,’ says Sugimoto to describe the series. This ray of pure white light looks at you from inside these century-old theaters, which have a hypnotic effect you cannot put your finger on. A similar effect transpires when you look at the artist’s Seascapes series.

‘Would we find an image we share in common if we go back 100,000 years in human consciousness?’ This was the question that got Sugimoto going and choosing the horizon line as one of the most basic scenes. Sugimoto associates this landscape with the beginning of human consciousness, a fascinating horizon line separating the sea and the sky right in the middle of the frame. Shot in different parts of the world for more than forty years, Seascapes remind us that the fragments of hundreds of thousands of years of human evolution are hidden somewhere in all of us, making us believe that staring at the sea could take us back in time. I must have spent at least half an hour looking at these photographs, which remind me of Mark Rothko canvases and Sol Lewitt’s Praiano photographs.

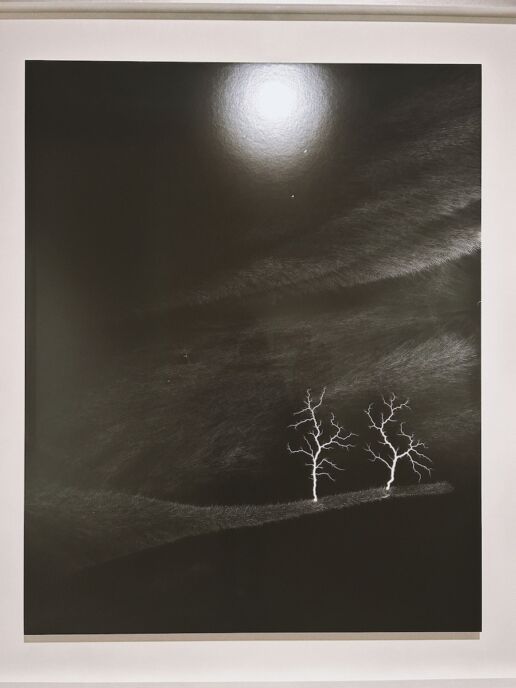

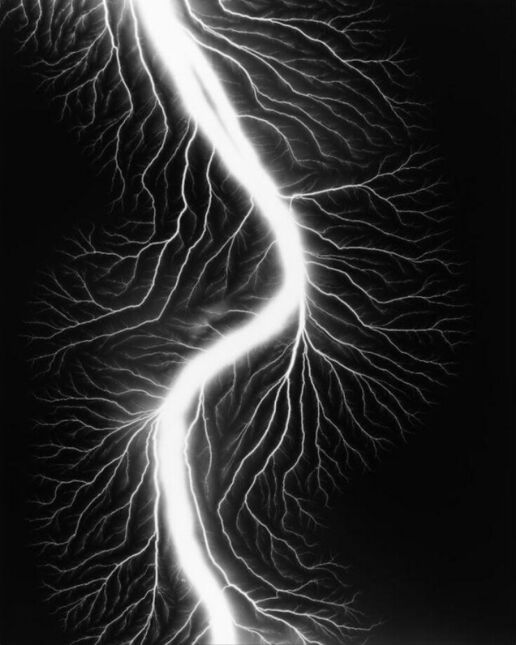

His fascination with the fundamental dynamics governing natural phenomena is perhaps the earliest of the recurring themes in Sugimoto’s work. At first glance, the visuals might look like a lightning bolt or two trees in an ancient forest. Still, when you realize they are created by an electric current from a Van De Graaff 400,000-volt generator circulating directly on the film, you feel like you have been electrocuted. Staring at bright block-color photographs inside frames that dwarf you demands a little time for your senses to adjust to what you see. The images depict the hues of light that Sugimoto observed through a prism in his Tokyo studio. Using a Polaroid camera, the artist recorded segments of the rainbow spectrum projected into a dark room, paying particular attention to the gaps and distances between hues. The resulting photographs are vibrant, almost sculptural images of unadulterated light.

‘The world is filled with countless colors, so why did natural science insist on just seven? I could split red into an infinity of reds.’

Combining the everlasting curiosity of his inner child with his immaculate technique, Hiroshi Sugimoto still seeks answers to questions that may have crossed all our minds, even if only briefly. His work is a constant reminder that we need to go beyond the obvious to arrive at a place we perhaps never thought we could get to. Whether making a dead polar bear look alive, creating trees from electric currents, or turning a two-hour film into a giant light source, Sugimoto creates photographs that often present devious objects to people who want to be deceived. By reminding us of our insistence on believing what we see, they expose our fragility. The artist hopes that taking a long look at the skyline we share with horses will one day compel humanity to question itself and why it ruthlessly abuses nature. Sugimoto bides his time by teaching his audience that looking does not always mean seeing and that seeing requires time and effort, bringing us a step closer to radically changing our perspectives.