Olgaç Bozalp is Pursuing His Dreams

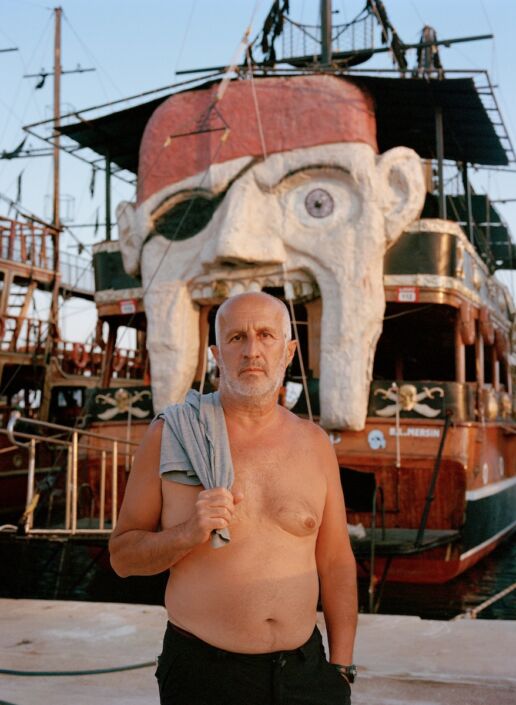

London-based multidisciplinary artist Olgaç Bozalp’s aesthetic choices bear clear traces of the nomadic spirit inherited from his father, subtle details from his hometown, the reflections of a formal training in acting, and the multiculturality of London, where he settled at the age of 18. Wandering through Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, photographing people, places, and stories, Bozalp relates different experiences while challenging the Western notions of hegemonic beauty. Olgaç Bozalp has been on our radar for a long time and we are delighted to finally find the opportunity to talk with him about his vision, uncompromising style and plans for the future...Photographs: Olgaç BOZALP

– What got you into photography? How did you discover your own visual style?

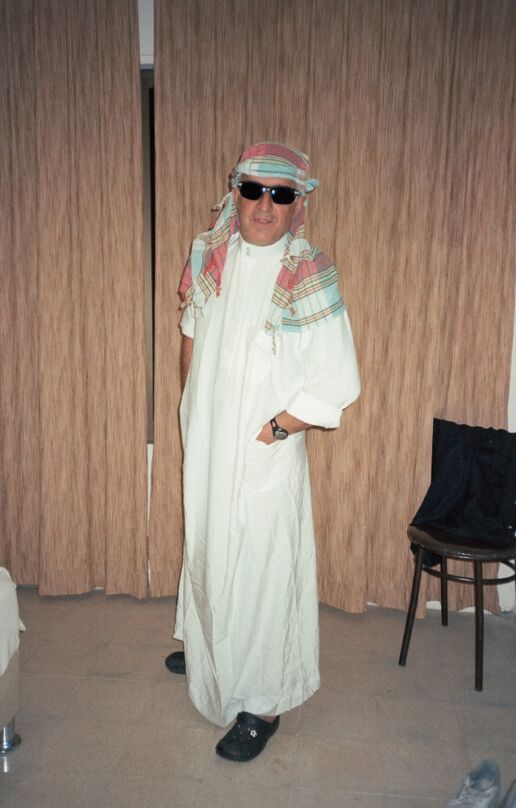

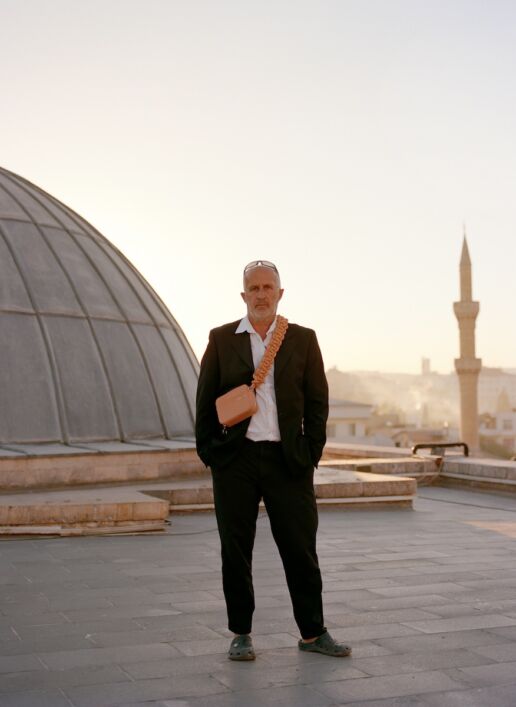

It was all very spontaneous, actually. I was studying acting in Cyprus. I had this thing where I would photograph myself as different characters using make-up. Then I started photographing my friends from class. I think that formal training in acting helped me build my style. Looking back, I see this as some sort of practice period. I wasn’t involved in photography when I first arrived in the UK. I started taking photos a couple of years later but I was still lacking a style. I found work doing fashion shoots and my main strategy was to photograph famous names. I believed that working with famous models would also make me famous. This phase took 4-5 years and I did work with famous names; Hollywood celebrities, singers, TV actors… but I wasn’t happy, my career was far from where I wanted it to be. In 2016, I made a clean start. I decided to create something myself instead of creating an identity through someone else. I hadn’t travelled that much until then. I left England for six months and went to Indonesia, and from there I returned to Turkey where I worked for a while. Then I went to Jordan with my father and I started photographing him. The work I produced during this period was the most well-received until now. My first series ‘Dad and His Jordanian Friends’ was followed by the ‘Istanbul Gucci’ series. Antidote Magazine must have liked my work because they approached me with a proposal. They had this concept where one photographer would take all the photos in the magazine. I told them that I wanted to travel, to find locations and models myself. I travelled across six or seven Middle Eastern countries with the budget they gave me. I can say that this is how my current aesthetic understanding started to develop. I like that my works involve a sense of humour. These are the photos I took with my father… I also work on themes such as personal journeys and travel. On the one hand, I also have abstract works.

– You also have interests in film, installation and art direction. Does multi-disciplinary work force you to split into multiple projects?

I love making movies and shooting videos, provided that it is within reason. There is always a degree of art direction in my work. Sometimes I build the entire set myself. I think these areas are not too isolated from one another.

-You have worked with brands including Carven, Hugo Boss, Dilara Fındıkoğlu, Camper, and Alexander McQueen. How do you balance commercial work with your artist identity?

I don’t try to strike a balance. I always preferred to photograph brands without changing what I was doing. I’ve always wanted to include something from different places and cultures. Many photographers determine and change their styles according to what the brand demands. I never did that. Of course, it was difficult to get my foot in the door. I was short on money for a long time. However, now I have a certain reputation, my work is better understood, and I can do things the way I want. It is important that the person has an aesthetic understanding. Then you can work as an artist, not just someone who takes photographs of clothes.

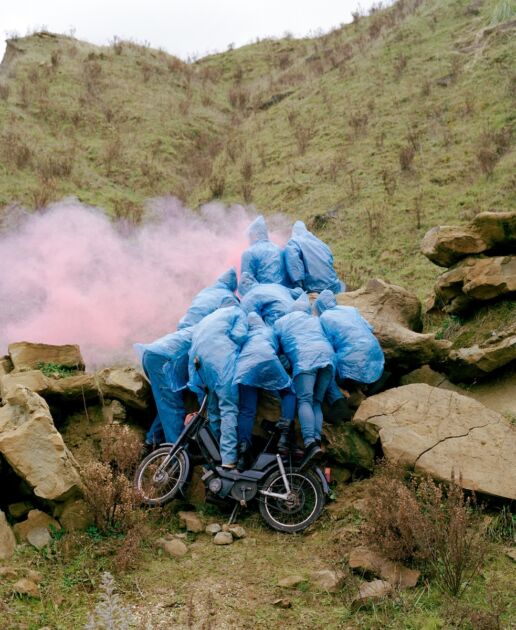

– What about your Nepal adventure and the “Buddha was born here” project that followed. How did it all start? You even thought of not taking your camera with you and ended up with zines sold all over the world?

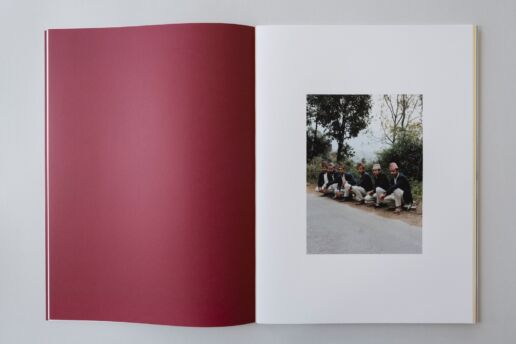

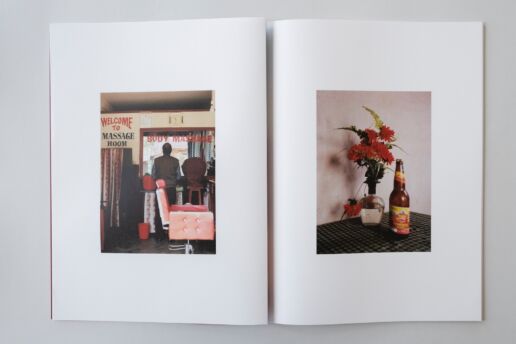

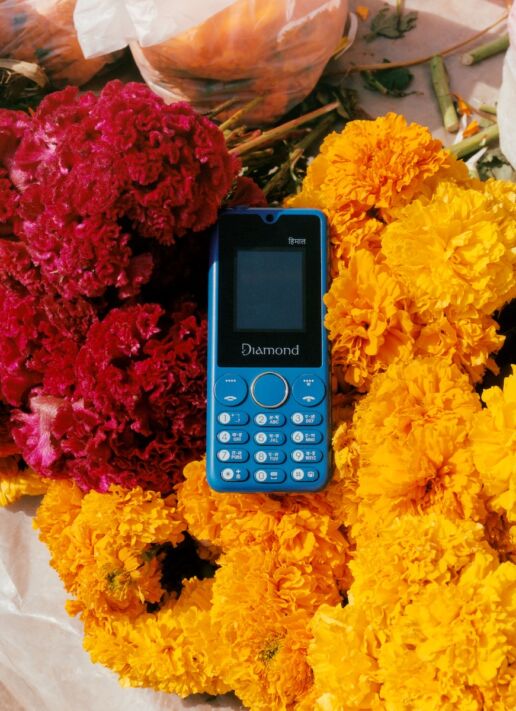

It was a period where I was questioning myself a lot. I had been to so many places for commercials lately that I started to think that I shouldn’t have to take photos on all my travels. I kept thinking about what I was doing and why. Maybe I would learn something and this would give me a whole new perspective in photo shoots to come. Nepal had always been a place I wanted to go. The spiritual aspect intrigued me. It all happened in a week, I decided to go, bought my ticket and left. I normally go fully equipped when I travel. I’m bound to take a spare camera and equipment. After all, films and cameras can play up. It’s happened to me a lot. But this time I didn’t care. Without any plans, I just bought 18 rolls for my camera and off I went. I stayed in Nepal for about a month. I didn’t take any pictures for the first few days, regretting that I even went there. Then I started to travel around the country. I was delighted to see that many things I try to stage in my work existed here naturally, blended into daily life. The colours and people’s take on life were intriguing. I had such a wonderful spiritual experience that how my photos turned out had no significance. The photos could be good or bad. I went there and had an experience. I was sure that I would materialise it no matter what. I mean, I had decided to create a zine before seeing the photos. Laconic texts written on the backs of long-distance trucks are a familiar sight in Turkey and I was surprised to see so many of them in Nepal. This is where the name “Buddha was born here” comes from. I saw this slogan on the back of many trucks in different fonts. This became the title of my series, partly due to my affinity for it in Turkey.

– How do the people, places and stories in your images that contradict mainstream concepts of beauty in the Middle East, Asia and Africa interact with the Western audience? What are the reactions?

We have been shaped to have a general understanding of beauty from a young age. However, you sell products to people who do not conform to this understanding, but they are not represented. Brands fail to show the faces of the people living where I was born and raised for example. Many different languages are spoken in the UK. Walk down any street and you will see dozens of different ethnic identities. While this is how it is here, it is wrong to experience this inside and not reflect it outside. I want to change this perception and perspective. I don’t want to shoot models, there are ample amounts of photographers who shoot the most beautiful models in the world. I like to photograph people, the unexpected faces in the places I go to. Anyone can wear a dress, there is no rule stipulating that it must be a model. The mainstream perception of beauty has lost significance in recent years. This shift helped my work to receive more positive reactions, but it wasn’t easy to get established. The agency I was working for was putting pressure on me to photograph ‘beautiful’ people. One of my series that was shot with great difficulty was censored by a magazine. A project I wanted to shoot in Turkey was shelved because they didn’t want to portray a Muslim country. One day I would really like to write about all of this.

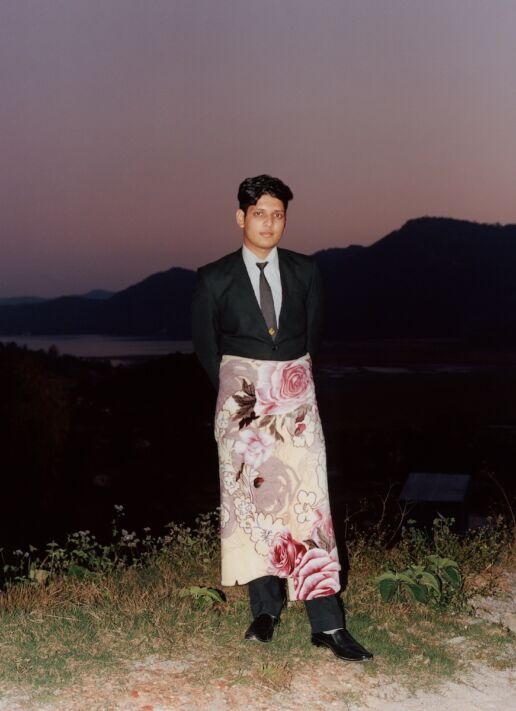

– Your father must be the person you shoot most. Apart from the visual experience with the locations, lights, details and colours, I found myself smiling looking at the photos of your father taken between 2016-2021. I don’t regard your father as an ordinary model. What is his role in your compositions?

My father is a tradesman who has nothing to do with photography or art. He always told me that photography was a hobby. But I think he played a key role in the development of my style. He’s been to 70-75 countries. I inherited my passion for travel from him. For example, it was my father who took me to Japan for the first time. It was also his idea to go to Jordan. I was working with models when we went to Jordan together in 2016. I was regretting that I didn’t have a model with me but then it dawned on me. My father was here and he could be my model. He probably videotaped and photographed every moment since my childhood. Now, I wanted to do the same to him. That is how the “Dad and His Jordanian Friends” series started and continues for the last six years. Travel plans were put on hold due to the pandemic, so we shot our latest project ‘Dad: On his Search for Hüseyin’ in Turkey. I recently sent him a camera and asked him to shoot himself, leaving the creative side entirely to him. I plan to prepare a book on it in the future. You have a point, my father is constantly giving ideas while I’m shooting, he puts his nose into everything. We even argue. I might not like them at first but some of his ideas turn out to give excellent results. For example, the photos inside the safes in the ‘Dad: On his Search for Hüseyin’ series was an idea of his inspired by another photo of mine. He is witty and humorous by character. It’s nice to see that this is reflected in the photos, and it’s not just a personal feeling. Interestingly enough, I always wanted to shoot celebrities, but my breakthrough came when I shot my father.

-What is next for you?

I’m preparing a book on the “Home: Leaving one for Another” series. I’ve been working on this for four years. I’ve taken a photograph for this series in every country I’ve been to. I wrapped up the last part last year and will be out in November. There is the FOAM exhibition on September 15. I am preparing for that now. I want to prepare a book on my father’s shots. In terms of my career, I would like to do more work for galleries and museums. Unfortunately, with the exception of a few copies of my book on Nepal kept at Odunpazarı Modern Museum (OMM), I haven’t done a lot of work in Turkey. I would love to do more soon.

Olgaç Bozalp’s zine on Nepal “BUDDHA WAS BORN HERE” is now available at Sanayi313 store and e-shop.